The Church has been called ‘the Fifth Gospel’ and sometimes in our services we include an extra Gospel reading – from the Gospel of St Luke’s West Holloway. On Sunday March 3rd we heard a reading from the Gospel of Gary.

‘I work in a supermarket warehouse where I pack food for internet shoppers. I get out of bed about 2.30 am, start my shift at 3.45 and work till 11.30. The warehouse is huge, full of all the domestic goods you can imagine. I wear an AMT on my arm, a machine that tells me what customers have ordered, where to walk to collect it and which conveyor to put it on. If it sends me, say, to Aisle 26 in Zone 4 for the skimmed milk, while I’m there I’ll also collect whatever else the customer has ordered from Zone 4. Then the AMT points me to another aisle for shampoo or mince meat or yoghurt.

If you get through an order quickly, you might have a minute to chat before the managers notice. I work with a very argumentative atheist and a very argumentative Jehovah’s Witness. The atheist is always saying ‘science disproves God’ and the Jehovah’s Witness always disagrees. As I can’t really get away from them I usually end up getting dragged in but I think God made science. What’s the problem? Why can’t God and science co-exist ?

The Jehovah’s Witness says it’s wrong to be gay. The atheist says Church is conformist. I tell them both they should come to St Luke’s where you can be gay and you don’t have to conform. I’m quite happy they know I’m a Christian, I’m not embarrassed about it.

With a proper job, me and Katya can save up for our wedding - now everyone can stop asking us when we’re getting married. We met as students at Chicken Shed Theatre Company and Dave is marrying us at St Luke’s which is good because I first came to church here when I was six weeks old. At St Luke’s there’s ‘Big Gary’, who’s a painter and decorator, and - because people have seen me grow up - there's me, who people call ‘Little Big Gary’. Although Big Gary’s not much bigger than me now.

Ivy, my great aunt, sits on the front row with her friends Sissy and Doreen. They always sit there. They should have a sign which says ‘Reserved’ on it. Ivy‘s been a regular for more than 10 years but she first started coming with her sister Ethel, my Nan. They came to see me in the Nativity Play when I was six, after mum and I’d started coming regularly.

I loved the Nativity Plays and I was upset when I got too old to be in them. I played the Holy Spirit one year. Another year I was Joseph, another year a Big Issue salesman - I think that was a modern version of the Nativity. One year I remember the Virgin Mary gave birth to a rugby ball. That was the year England won the Rugby World Cup. That was another modern version.

I’m 23 now but Nativity plays, crèche and Sunday School are powerful memories for me. That’s how I got to know Wez and Tom and Ben and Kaveh. Kaveh could be pretty pumped up sometimes. He used to watch a lot of wrestling. Maybe he liked to use us as opponents. He left church for a long time, but I love it that he just turned up again a few years ago, as if he’d never been away, and he’s a changed person. He’s a brilliant musician too, I love it when he sits down at the piano after a service.

It worries me watching my Nan getting so frail. She can’t get to church at all now but Ivy makes sure she’s ok. She forgets a lot. She sometimes calls me Colin, my Dad’s name. Although, funnily enough, one thing she never forgets is to talk about our wedding. We’re a 40-minute drive from Holloway these days and some Sundays I go to see my Nan instead of coming to the service. I come down for coffee at the end.

People think of churches as being against things but what I like about St Luke’s is that there are lots of different kinds of people and we don’t judge them if they’re different in some way. You can come here whatever you believe, we will still accept you. Even if you’re not religious, come and have a coffee anyway. Nothing will be forced down your throat, make up your own mind. Katya brought her mother once and even she liked it.

I had trouble with my speech when I was young but doing drama games helped me and it got me interested in acting. I’m always the shy one. In a conversation I feel like I babble on too much. Sometimes - as myself - I don’t have the words to say but when you’re acting you have lines to learn so you always know what to say. Acting was how I found a more confident version of myself. After Performing Arts I studied Media Performance and I’d like to get into radio or TV. I’m a film buff. Some weeks I go to the cinema seven or eight times. I saw the new James Bond four times in a week. If my writing matures I’d like to be a film critic.

Colin, my dad isn’t a churchy person. I’ve always come to church with my mum Carol, although I’ve never asked her about her faith. It’s just what we do. As a kid I wasn’t baptised or christened so before my teens I made the decision to be baptized and confirmed on the same day. Being present at St Luke’s is important for me in feeling closer to God. It might be the bread and wine or a hymn or it might just be talking to people afterwards.

You don’t want to put everything on God because he’s got so much to do but it’s good to know he’s looking out for you, that there’s someone to show us a better way. I believe in a creator who designed us and when things are going bad I look to God for guidance. I see God like an old friend, someone you can turn to for a chat, even though he can’t answer you with words. I feel better for talking to God. It’s like being in a family where you know someone is always looking out for you. You’re in God’s family and God wants the best for you.

I’ve been coming to St Luke’s all my life and now I’m getting married here. It seems right. Maybe if Katya and I have children, they’ll be baptised and confirmed here like me. Maybe they’ll be in the Nativity Play like I was.’

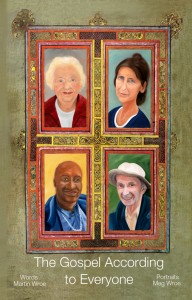

A collection of 12 stories like this from St Luke's can be found in The Gospel According To Everyone.